Rethinking Tools in MCP

If you’ve been above ground at any point in the last year you’ve probably gotten a whiff of the MCP vs CLI argument. It usually rests on the GitHub MCP server, which exposes dozens of tools endpoints and quickly overwhelms the context window of most agents. I’ve spent my fair bit of time trying to explain why people need to move on from the debate, agree that the design of the GitHub (and many other) MCP servers are wrong, and move on with pushing the next iteration of agent toolchain. With this latest installment I want to talk about an approach we adopted recently in Sentry’s MCP service that we’re calling skills (sorry in advance for the name conflict!).

Before we get into skills, it’s important to know how we got here. Early on, just like everyone else, we had a simple MCP service that exposed a handful of tools requiring a variety of permissions. Most of these tools weren’t harmful, but a few did perform write operations, and that led to some customers rightfully asking for a way to disable those. That then gradually expanded to customers asking to completely remove certain tools as they just weren’t getting value out of them, and they wanted to save the tokens. Again, another totally valid ask. Both of those resulted in a first iteration of skills that we called permissions, and mostly looked like normal OAuth scopes.

We designed these permissions to allow you to limit what the MCP service had access to. That had a secondary benefit of also limiting the tools that would get exposed in your session, as if you didn’t have the right scopes, there was no point in exposing the tool. A huge win, but it was still fundamentally connected to Sentry API, and its defined upstream scopes. We wanted to expand that from a set of permissions, to a set of behaviors. Permissions do not clearly signal the intent or use cases you’re after, but this new approach does. As an example, here’s permissions we had before:

- (defaults) - more or less all of the core read permissions

Issue Triage- gave youevent:write, letting you call theupdate_issuetoolProject Management- gave youproject:writeandteam:write

While this was already a half-attempt at a better abstraction, it was still exposing our API rather than building intent. This is the same issue you see in GitHub’s MCP, and while not nearly as pronounced, it’s the wrong design. In our use case, and most MCP implementations, we are trying to utilize this protocol as a way to give customers access to a set of tools to interact with our services. We are not trying to give them a bunch of new API endpoints - a new development kit - that they will then use to build a new application. So why do we keep exposing plain APIs, and those same API paradigms?

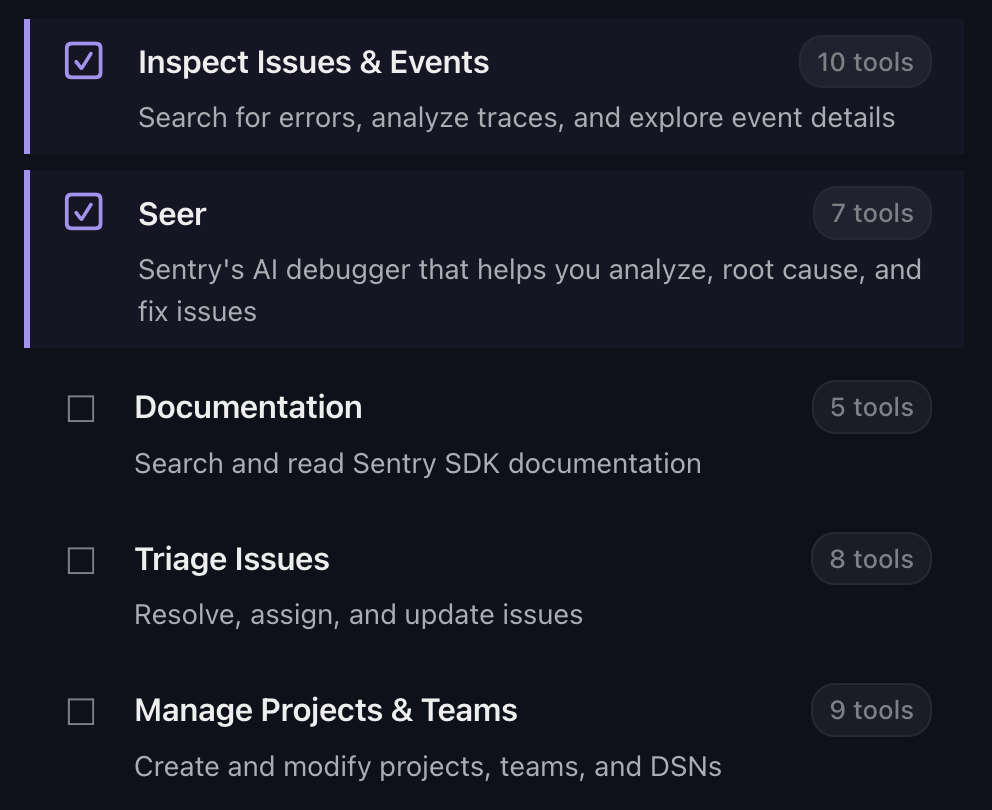

With the learnings we had from those permissions, and our creeping on using these more as a workflow optimization and less as a permission system, we had a clear path for improvement. That improvement was now what we call skills. We took the basis of the scopes system we already had and layered in a new virtual permission system on top that would take a skill (Issue Triage), define holistically which tools it needed (update_issue, get_issue_details, etc.), and expose that concept to the end user. Behind the scenes this was actually pretty straightforward, as we had some scaffolding for this already:

// update_issue()

defineTool({

// Our initial implementation defined which scopes a tool requires, which is

// still useful to understand which upstream (Sentry API) scopes are needed.

requiredScopes: ["event:write"],

// In addition they now also define which skills need access to the given tool.

// Note: This would be better defined within a skills definition tree, but for

// our codebase it was cleaner to keep the existing pattern.

skills: ["triage"],

handler: () => {

// ...

},

});What’s nice about this is we have now contained the entirety of outcomes users are after within these skill systems, and even though under the hood we’re still exposing a set of tools, we’re actually not constrained to that. Today we may give you get_issue_details and update_issue, but there’s no reason that we can’t (or shouldn’t) optimize this into an embedded subagent (triage_issue). That may not be true for every use case in MCP, but for Sentry we are explicitly designing this service as a coding agent peer, which allows us to make explicit decisions on how and what we are exposing to create the best experience.

We’ve also talked about taking this concept further if we wanted to expose a single “Sentry” MCP service that acted as a gateway. That is, we are likely going to have a number of agents in the very near future, and while some of them will make sense to run in your favorite coding agent, others will not. That means we could take this skills umbrella pattern and use it as a generalized solution to expose MCP toolchains to end users. There’s some pros and cons there, but the main benefits come down to minimizing the surface area (security and testing primarily).

Either way my guess is we’ll continue to see an evolution of this kind of pattern. You’ve already seen this within Claude Code in their own implementation of Skills. It’s a great way to compartmentalize a set of concepts, and in their case it’s effectively a subagent plus tools (similar to our Subagents with MCP approach I talked about before). It gives users something they understand and desire while also minimizing context bloat, permission creep, and general complexity or confusion on what the system’s intentions are.