On Pull Requests

You're viewing an archived post which may have broken links or images. If this post was valuable and you'd like me to restore it, let me know!

A recent conversation came up on Twitter that sparked some discussion about GitHub Pull Requests and code review.

I both work on a large number of open source projects, and also drove code review initiatves at Disqus and now support them at Dropbox. Given that, I thought I’d give some perspective on my thoughts of GitHub Pull Requests and how it fits with code review.

#What is a Pull Request?

(A quick tl;dr if you don’t use GitHub)

A pull request is simply a request to merge a patch. For example, if I want to contribute to an open source project on GitHub, my typical workflow would be:

- Fork (clone) the repository

- Create a new branch with my changes

- Submit a pull request to the original repository describing my changes

Once submitted users can then view and comment on my patch and anyone with commit rights can merge the patch.

This isn’t the only workflow for them, but it does accurately describe the functionality available.

#The Breakdown

I love Pull Requests for my open source projects. They’re simple, and they work very well. My open source projects also generally have no more than two or three maintainers. What I will focus on in this post is the point at which Pull Requests break down, and become too noisy to be an effective review tool. That number may vary, but I would say that once you hit a dozen engineers on a project, you’re probably already experiencing the pain.

Specifically, I will be comparing Phabricator to GitHub. There are alternatives, but in my review of the choices available around 18 months ago, nothing was at the same level as Phabricator.

#Pull Requests vs Code Reviews

What’s actually different? To start, let’s look at the basics when comparing them as tools specifically for doing code review.

Most systems generally start by creating a patch and uploading it to a remote server. On GitHub, this is done by pushing a remote branch in addition creating the pull request. Phabricator isn’t bound to a single version control system, so it abstracts this away in the form of a “Revision”. This revision is simply a raw patch with a bunch of metadata and is uploaded to the server via a command line tool.

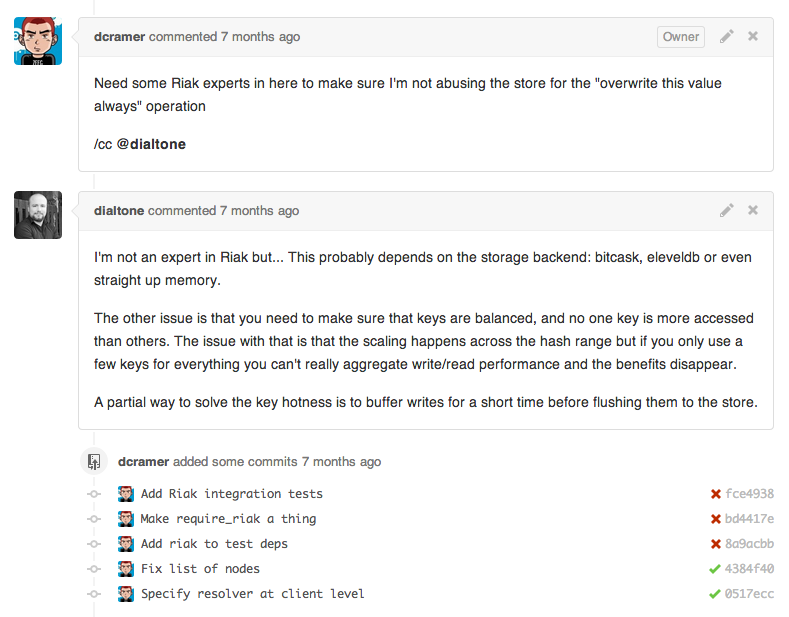

Now that we’ve pushed up a patch, we’ll see the first, and one of the most important differences: GitHub emails every single person who is subscribed to the repository. Inside of Phabricator there’s either some kind of explicit assignment (e.g. I want Bob to review this) or there’s implicit assignment based on any number of rules. Phabricator will then only notify the responsible people.

A couple of terminology you’ll want to get down:

- A GitHub Pull Request is approximately a Phabricator Revision

- A commit is approximately a Phabricator Diff (which is attached to a Revision)

#Code Ownership in Pull Requests

Given that the most important difference between GitHub Pull Requests and proper code review tools is the notifications, let’s step back and think about what that actually contributes to.

In GitHub, it’s very common that you might be a contributor to a repository but not subscribe to notifications. It’s completely reasonable. It works very well as long as you’re proactive about checking the pending requests. There’s no big issue there. The issue comes down to who is actually responsible for looking at the code.

Let’s take a simple example:

- Bob makes a change to ‘database.py’.

- Joe has notifications enabled, sees it’s about the database (which he isn’t responsible for) and archives the email

- Jim does the same as Joe.

- Billy has notifications disabled because most people don’t touch the database, and that’s all he cares about. He checks pending pull requests a few times a day.

- Bob eventually gets smart and puts “@billy” somewhere in a comment or the pull request itself, in hopes that Billy will look at the pending request.

- Billy looks at the request, but doesn’t have time to deal with it, and he’s hoping his team member Jane gets around to it first.

- Jane, also frustrated with email, only checks it a few times a day because it’s too noisy. She eventually checks it at the end of the day, and see’s @billy in the comments and assumes he’s going to take a look at it.

- Bob comes back the next day and starts flipping tables.

Take that example, and expand it to 100 engineers. Companies like Google, Facebook, and even Dropbox, have fairly massive repository sets. While you might think that’s the problem, there are many benefits (which I won’t cover in the slightest in this article). If you imagine getting an email for every patch from these hundred engineers, you can quickly see how you might start filtering out the email.

You can take the other side, and maybe you’re very outgoing and happy to review a lot of these patches, or just to archive the emails when they come in. Now imagine doing that 300 times a day, and then consider how much code you’ll actually be able to contribute.

#Code Ownership in Phabricator

While Phabricator is only a couple years old, it’s being very aggressively developed, and many would consider it the hands-down best choice for tooling that’s available publicly (ignoring that it’s completely free). It’s list of features has grown over the years, but even at its basic level it’s very beneficial in a company.

I talked about how a dozen engineers working on a project would already cause these situations to exist, but you could see a smaller project having similar issues. Imagine you have five engineers, one is purely doing frontend (JavaScript), three doing backend (Python), and one is doing sort-of operations. How likely is it that you think the operations guy cares about most of the code flying through his inbox? There’s absolutely no way to filter this within GitHub (without relying on the mentions hack).

In Phabricator we have numerous options for assignment, so I’ll describe a few that we employ at Dropbox.

#Explicit Assignment

When a team is small, it’s pretty easy to know who can review a piece of code. Phabricator supports very simple “I want X or Y to review this”. It’s also an OR condition, and its never “I need both X and Y to review it”. While this may be unfamiliar from systems that require N+ reviewers, it has worked very well in all of my experiences.

#Implicit Assignment

Phabricator provides a number of systems that let you describe code ownership or otherwise “Bob is responsible for this”. These systems include being able to identify repositories, paths in repositories, even contents of a file, and assigning Bob as a reviewer automatically.

#Team Assignment

Another option Phabricator provides is the ability to use teams in both of the above fashions. This means that you can setup a team (“Python Backend”) and simply assign code reviews to that group of people. This becomes increasingly important in a larger organization where you might overlap with multiple teams but not be familiar with their day-to-day responsibilities, or even who’s really on the team.

#Mandatory Assignment

Recently we sponsored a feature in Phabricator which added the concept of “Blocking Reviewers”. You might look at this and think “wow, that’s gotta be annoying”, but we use it for things like security controls and ensuring that anytime X changes, it gets reviewed by someone from team Y.

#Audits and Metadata

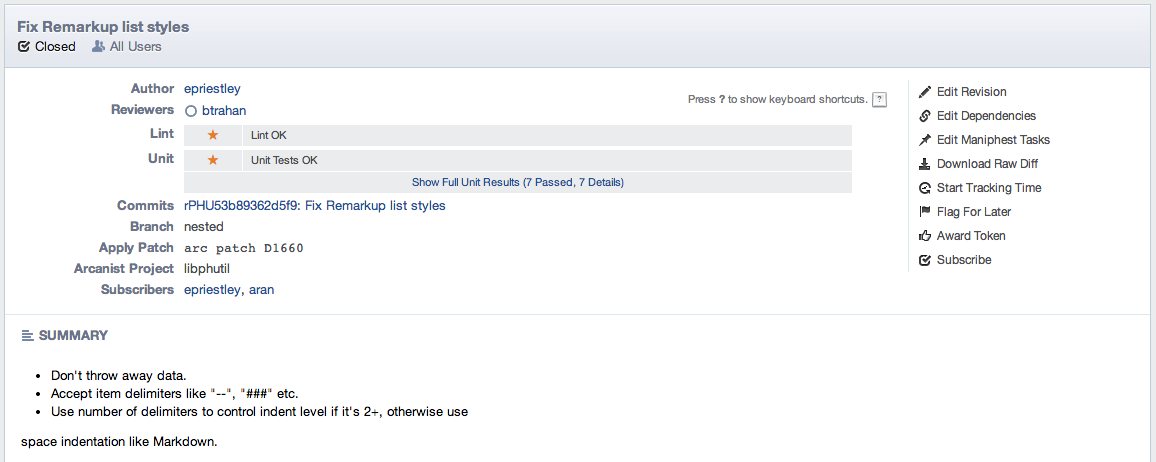

One of the first things you’ll notice that’s extremely different in Phabricator is how patches actually work. Before describing that, let’s take a look at the metadata GitHub provides:

- Title

- Message

- Subscribers (via mention hacks)

While both of those are useful, they’re basically lost as soon as you merge the pull request (though you could dig through history if you needed to).

Within Phabricator we have a considerable amount more of metadata, in addition to it appending some of it within your actual commit history.

These include:

- A link to code review object

- Assigned Reviewers

- Reviewed by (who actually accepted it)

- Who was subscribed (CCs)

- [literally anything else you want]

Now this might seem noisy in some cases (I personally don’t ever dig through the commit log), there’s also the secondary aspects that Phabricator provides around it: the ability to audit history.

I mentioned that one use case of team assignment that we employ is for security reviews. I probably don’t need to tell you how important it is that we know which items required security review, which ones didn’t, and if in some rare case it happens, which ones should have been.

You probably use Gmail and are familiar with it’s filters. Phabricator provides something similar to this called Herald. It allows you to setup rules on any number of things, including diffs (code reviews) and commits. More importantly it allows you to perform some very useful operations on the result, such as denying the commit (literally blocking a push), assigning reviewers/cc/etc, and sending emails. This fits in both from an audit perspective all the way back to our code review processes.

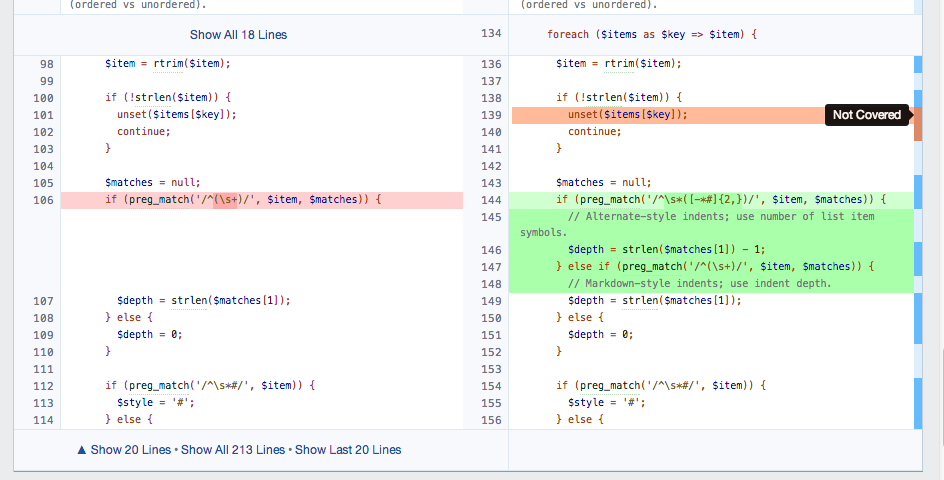

#Test and Coverage Reporting

There are a number of projects out there that integrate with GitHub and provide some really nice features. Travis CI, Coveralls, and far too many others to list. They’re usually drop-in or require just minor tweaks. Some of them even go as far as telling you that a pull request has issues (e.g. failed to pass tests).

Nice, right? One look at some of the drop-in integration in Phabricator will have you in awe. Let’s first point out that it’s completely integrated, isolated to a diff (that is, a single version of the patch). What does that actually look like?

While this might require a bit of work on your side, there are several drop-in integrations available (such as py.test) that can do this for you.

#Tidbits

A few other highlights of Phabricator:

- A beautiful command line tool for working with patches (Arcanist)

- Early repository hosting and mirroring support

- Preventing ‘force push’

- Blocking a commit until its accepted

- Side-by-side diffs in code reviews

- VCS-platform agnostic (svn, hg, and git support currently)

- It’s also mostly workflow-agnostic

- Audit capabilities (e.g. post-commit code review)

- Media attachments / image macros (e.g. cat gifs everywhere)

- A non-perfect bug tracker that is 10% better than GitHub and 900000% less complicated than Jira

- Integrated pastebin (not as fancy as gist, but you can

pbpaste | arc paste) - Rough (UI-wise), but very thorough ACLs that let you butcher your install as much as your heart desires.

- A few minor email actions (e.g. respond with ‘!accept’ to accept a patch)

#In Closing

Pull Requests can work for small teams and are really useful when you’re actually working with a repository that’s hosted on GitHub and public. That said, if you’re working on code that’s not open source (and/or it’s not a personal project), I would highly recommend taking a look at Phabricator. Even if your company (i.e. Dropbox) has open source projects, there’s no reason you can’t rely on both. Let the public submit patches via Pull Requests, but keep control of things using real tooling internally.